by Dr. Sunny Sue Chang Jonas

Rural spaces no longer include only multi-generational, homestead-owning families. They include a different sort of marginalized population—one that feels financially and vocationally in transition. This has been true for a while with “migrant worker” populations— families that move with agricultural, crop-based work (e.g. from strawberries in Oregon, to apples in Washington, to almonds in California), or even communities committed to moving for the intentional liminal freedoms they provide, as featured in the movie Nomadland. Refugee youth as another example, also live in the liminal space of the “now” and “not yet”—toggling between two or more linguistic and cultural communities, sometimes even translating for their parents and family members; this is also like our toggling between the “codes,” norms, and values of our heavenly citizenship and earthly dwelling/limitations. How do we live in these liminal spaces, and how do we serve others living in their own, intersectional liminal spaces?

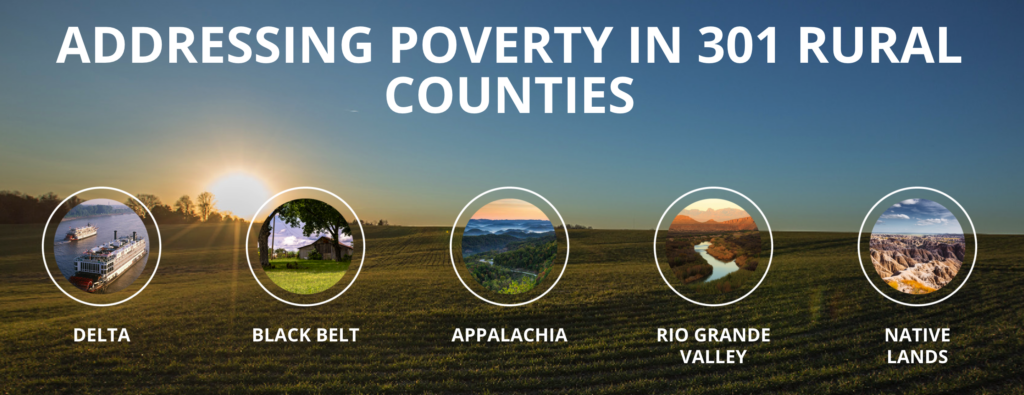

Meet Dr. Rev. Jason Coker. He was introduced to Liberation Theology and the idea of liminal spaces for marginalized populations at Yale Divinity School. Dr. Coker is the National Director of Together for Hope. Together for Hope, affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship, oversees 301 counties of “persistent poverty.” At a recent conference for Baptist pastors, Dr. Coker shared some of his thoughts about supporting rural communities in theirs and our, liminal spaces. Referencing this passage from the book of Mark, he offered some reflections on liminal spaces for rural communities and beyond:

A furious squall came up, and the waves broke over the boat, so that it was nearly swamped. Jesus was in the stern, sleeping on a cushion. The disciples woke him and said to him, “Teacher, don’t you care if we drown?”He got up, rebuked the wind and said to the waves,“Quiet! Be still!” Then the wind died down and it was completely calm.

(Mark 4:37-40)

“Liminal spaces are holy because they are filled with uncertainty, doubt, fear, and turbulence. It is temporary space—space you are moving through. It is defined by transience. It is life on a line, having both fear and need. That’s where we find Jesus and the disciples in this passage from Mark. They are crossing over from one political region to another and they are on the water in liminal space—that space in-between. They were secretly crossing a border at night, moving from Jewish territory to Gentile territory. Leticia Guardiola Saenz characterizes this common movement of Jesus as a Border Crosser. Her work shows that Jesus usually causes a disturbance in one region and then “crosses over to the other side” seemingly escaping the trouble from one place and seeking refuge in another place. This border crossing defines Jesus’ ministry and miracles. Using Border Theory, Guardiola Saenz not only highlights Jesus as a border crosser, but also shows how Jesus can give hope to all those who find themselves on the border—in liminal spaces of uncertainty and fear. Her work positions Jesus always with immigrants, always on the border, always with those who fear, always with those who live in the holy and dangerous space.“

Many of us are investing in our own, distinct, local communities. For Dr. Rev. Coker, these are the congregations that he supports and leads. For us, it is our particular home, church, and work spaces that are in their own, unique liminal spaces. His assertion that “hope is not an ethereal idea—it’s putting your hands to the work… holding that middle space—” is parallel to our primary charges as Christians: to love God and to love others. We love God in his identity as Border Crosser and in His image, we embody the strengths and liminality of being Border Crossers as well.