I occasionally speak to churches and other Christian gatherings about my research, on the history of American religion, crime, and punishment. After I walk through the history of Christian contributions to the creation and maintenance of America’s systems of mass incarceration, I often receive some form of the following question during Q&A: given this sobering history, is there hope?

It’s a great question, and there are a number of concerns I see embedded within in that I wrestle with myself. Is there hope that the United States can break its addiction to locking up immense numbers of people, often in extremely grim conditions? Is there hope for the communities that bear the burden of over-policing and criminalization? Can American Christians, in turn, break our addiction to theologies of retribution, support for “law and order” politics, and, particularly for white evangelicals, high degree of confidence in the police? What can we do now, and where should we even start?

A high degree of pessimism on these matters is understandable. Despite heightened public awareness of the problems of mass incarceration, the United States still has the world’s highest incarceration rate. Recent reforms, while a step in the right direction, are modest at best. Politicians on both right and the left remain unwilling to accept radical alterations to our practices of policing, prosecution, and punishment, a reality in keeping with much of the bipartisan support for the expansion of the carceral state throughout the twentieth century. Violence and crime remain problems facing many communities, evidence that more policing and prosecution ultimately does not solve root problems of poverty, racism, and lack of educational opportunities (indeed, they exacerbate them).

But despite these sobering realities, there is hope. And here is the hope I try to convey to fellow Christians and what I remind myself of when I consider these challenges.

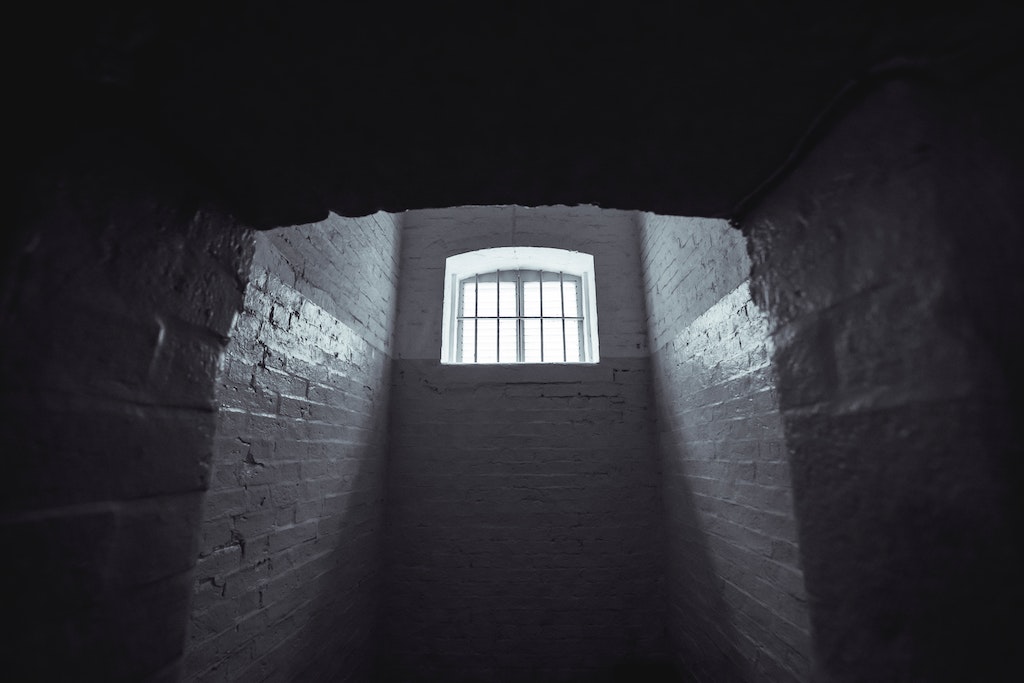

Fundamentally there is hope because we worship a God who has promised to bring freedom to the prisoners. We follow an executed Savior who went to the cross, an instrument of punishment, and in his resurrection defeated the crucifying powers that bind and take life. Jesus was put to death between two criminals, who theologian Karl Barth called “the first Christian fellowship, the first certain, indissoluble and indestructible Christian community.” We worship a God who cares about restoration of sinners and of broken relationships, and the well-being of those who society might like to forget. We are inheritors of a faith of incarcerated apostles and saints, and of offenders who have their lives restored through God’s mercy and grace. God is concerned with the spaces of punishment, and the people caught up inside of them. And in God’s Kingdom, these spaces that isolate and brutalize do not have the last word. As Hannah Bowman has written, “our Christian hope for a world without prisons rests on the promise of God.”

There is also hope because our current system is not timeless and, unlike the Kingdom of God, it is not eternal. Our modes of policing and punishment are human inventions. Though understanding the unintended consequences and unrealized aspirations that went into building this system is important, ultimately our criminal justice system works the way it does because of the choices we have made (and are making) to create and maintain it. Over-policing, overreliance on plea bargaining, harsh prison sentences, the challenges of re-entry, the brutality and frustrations on prison life, capital punishment – all of these aspects of the carceral state are highly imposing and complex problems to be solved, to be sure. But though the carceral state is a massive, multi-floored edifice, it is nonetheless a construction. It is a structure that we have built, and it is a structure that can be torn down. The question is whether, in our deconstruction, we will simply swap out a few lightbulbs or work for something completely transformative, a system that truly addresses the needs of victims and incarcerated people alike. As Joshua Dubler and Vincent Lloyd remind us, “One day, not too long from now, there will be no more prisons.” Therefore, we must ask whether the work we are doing now is working towards that future, or simply reinforcing the status quo.

In my own life, I have seen many such hopeful examples of Christian faithfulness of work realizing God’s hopeful future amidst a punitive society. Bryan Stevenson is a name well-known to many, famous for his book Just Mercy and his organization Equal Justice Initiative, which challenges inhumane prison conditions and unjust sentencing practices. Most impressive to me is Stevenson and EJI’s deep, public awareness of history and the role of racism in the formation of our justice system. However, for Stevenson, these systemic realities are not ultimately overwhelming or an excuse to forgo personal engagement. His repeated refrain is for concerned citizens (and Christians) to “get proximate” to the problems of injustice. Though not a panacea, proximity is a crucial first step in raising our awareness and, most importantly, pushing us to listen to the voices of those caught up in the justice system.

Less well-known but no less important is the work of Christian prison education programs, like North Park Theological Seminary’s School of Restorative Arts. In North Park’s programs at Stateville Correctional Center and Logan Correctional Center in Illinois, free and incarcerated students take courses together on topics such as theology, history, conflict transformation, and race. Educational programs like North Park’s work to break down walls that exist between Christians inside and outside the prison walls, as well as the barriers that limit the potential of incarcerated people. As School of Restorative Arts Director Michelle Clifton-Soderstrom told me, “We believe in prison abolition, and our way of playing our part is through education and extra-curricular advocacy with community partners.” Incarcerated students have spoken of the transformative and live-giving effects of North Park’s courses: “I have so much hope. This is something that is getting me prepared for something that God has in store for me.”

Finally, the organization Abolition Apostles offers a model of Christian prison ministry that is consciously critical of American systems of punishment and that foregrounds the voices of those on the inside. Founded by David Brazil and Sarah Pritchard, the ministry supports more than 3000 incarcerated people across the country and is currently working to develop regional chapters and a fund a hospitality house ministry near Louisiana State Penitentiary. Abolition Apostles’ nationwide pen pal letter-writing network, which I am blessed to be a part of, opens the door for new relationships and opportunities for solidarity with those on the inside.

These are organizations and people who are working to chart alternative, life-giving paths to our present system and, in Christian terms, gesturing towards God’s coming kingdom. The present challenges of mass incarceration can seem overwhelming, but we have an opportunity to join this liberating work.

As you consider your response to the often overwhelming challenges of our nation’s criminal justice system, do not lose hope. Look to organizations doing good work for inspiration and ideas, and the faithful voices that point to alternative ways of thinking about justice. Most of all, look to the crucified Lord, who in his death and resurrection abolished the powers of violence, and who offers us an invitation to join him in this revolutionary work.

We invite you to respond by…

- Purchasing God’s Law and Order (Griffith) and/or Rethinking Incarceration (Gilliard).

- Attending a local Locked in Solidarity event (taking place around the nation between February 6-13, 2022). Learn more here.

- Hosting a Locked in Solidarity event.

- Learn how your church can help end mass incarceration through our coaching session here.

- Have your congregation and/or ministry leaders study and discuss LMDJ’s Criminal Justice and the Church curriculum.

- Watch the film Just Mercy and use this community discussion guide.

About Aaron Griffith

Aaron Griffith is an assistant professor of history at Whitworth University. He is the author of God’s Law and Order: The Politics of Punishment in Evangelical America. He has published academic articles in Religions and Fides et Historia and written for popular publications such as The Washington Post, Christianity Today, and Religion News Service.

God’s Law and Order: The Politics of Punishment in Evangelical America explores how American evangelical Christians shaped—and were shaped by—the American criminal justice system. A “religious history of mass incarceration,” the book investigates evangelical influence in anti-crime politics, prison ministry, and criminal justice reform in the twentieth century. His book won Christianity Today’s Book of the Year Award for the history and biography category. (You can find Christianity Today’s book review here.)